The Art of Time in Fiction, and in Life

Issue 7: Then, now, later

“All art is a negotiation with time,” begins Gina Chung in her One Story craft lecture, Tempo & Rhythm: Manipulating Time in Fiction. “Maybe this is because we have trouble with the passage of time in real life,” she jokes. This is over Zoom, so we are all mute. The silence swells for a brief moment. I scan the grid of participants—rectangular facsimiles of people’s faces—searching for a silhouette of a smile, a lingering laugh, any marks of mirth. Chung chuckles herself forward, continuing, “Time in fiction is very flexible, and time equals control. If you control time, then you control the sequence of events in your narrative.” Perhaps she has hit too close to home.

When I started writing this issue (literally months ago, why am I like this), I had a very contained idea in mind. I was going to steal like an artist—from Gina Chung and Joan Silber—and summarize the techniques I learned from both Chung’s lecture and Silber’s craft book, The Art of Time in Fiction: As Long As It Takes, then discuss how I applied these to a short story I was working on. In fact, I had already done a version of this for a Powerpoint party with friends, so I mistakenly thought it would take me no ~time~ at all.

But the more I created this form of attention to the “art of time,” the more I saw, the more I connected things back to this lens. I wanted to interrogate more about our negotiation with time, to read, watch, and experience more art on the subject of time. I had more things I wanted to say. And of course, this was all happening while I continued to go forward in the time of my own lived life, moving between “then and now and later,” (which is how Silber refers to a story’s arrangement of events), putting pieces together that could only be assembled from an angle of retrospect. This universal experience with time passing in our own lived lives then led me to reflect on how I make moments of meaning in my real days, weeks, years, because unlike in fiction writing where time is both a writer’s canvas and medium, in real life, time is an unwavering phenomenon, a looming presence, ever moving in one inevitable direction.

Each novel creates its own “form of attention,” a term Matt Bell uses in his book, Refuse to be Done: How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts. Creating these different forms of attention gives us a unique way of seeing and experiencing the world, and while Bell focuses on the form of attention a novel demands, other creative projects or personal obsessions or a silly newsletter issue also command their own forms. This is my attempt at distilling the fascination of my attention for the last few months. Am I… Christopher Nolan?

*plays Hans Zimmer’s Time*

In Fiction

Tempo & Rhythm: Manipulating Time in Fiction with Gina Chung

Chung defines tempo as the pace, how fast a piece of music moves, or how fast your heart pumps, while rhythm is the pattern of how that tempo manifests, like the distinct pattern of a heartbeat’s contractions and relaxations. As applied to fiction, tempo is the pacing of the story; rhythm is the words and sentences you use within that pacing. The rhythm of a narrative is how it looks and feels on the page.

Chung detailed four different techniques of manipulating time in fiction, each with close readings to illustrate the craft in practice: speeding up time, slowing down time, oscillating through time, and collapsing/freezing time. What I particularly enjoyed about her teaching style was her close attention to examining the effect of certain craft choices, looking at both the why and how certain words, verb tenses, or imagery contribute to varying tempos and rhythms.

Time Narrated versus Time of Narration from Matt Bell

Where and when a story is being told is another temporal consideration that shapes the overall narrative on the page. In Refuse to Be Done, Bell defines “time narrated as the amount of time the action of your novel covers; time of narration is the moment in time from which the story is told.” Choosing different time durations narrated, or different moments to tell the story from will open different possibilities for a story, as these choices will constrain the storytelling options for “reflection, exposition, and authority,” Bell summarizes.

The Art of Time in Fiction: As Long As It Takes by Joan Silber

“Time draws the shape of stories,” Silber opens. “A story is entirely determined by what portion of time it chooses to narrate. Where the teller begins and ends a tale decides what its point is, how it gathers meaning.”

Chung quoted Silber at the beginning of her lecture, recommending her craft book from Graywolf Press in “The Art of Series.” While Chung focused on techniques to manipulate time on the page, Silber considers the question of duration, the span of time selected for a story’s events. Her basic categories for time spans, “handy labels” as Silber calls them, are not meant to be exhaustive, as “there’s no tent big enough to cover what fiction can do with time.”

- Classic time: A brief, natural span—a month, a season, a year—handled in scene-and-summary. Selected reading: The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Long time: Spanning decades, lifetimes, generations. Selected reading: “The Darling” by Anton Chekhov; To Live by Yu Hua; To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

- Switchback time: Moving back and forth among points in past and present, using shifts in an order that doesn’t give dominance to any one particular time. Selected reading: “A Real Life” by Alice Munro; “Sonny’s Blues” by James Baldwin

- Slowed time: Brief instants in detail, where a very short piece of action is examined very, very closely. Selected reading: “Chef’s House” by Raymond Carver; “The Thirst” by Nawal al-Saadawi

- Fabulous time: A way to think about non-realistic fiction, where laws of space and time don’t operate according to the rules of our world. Selected reading: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez; The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

Silber closes out with an essay, “Time as Subject,” examining different story archetypes whose plots directly address remembering, forgetting, revising, and wasting time. In her examination of this “dilemma of transience” and how mortality gives life meaning, I can’t help but think about the wasted, ruined, unled, well-led lives in fiction, and ask the question of what “wasted time” or “well-used” time looks like in my lived life. Probably best to not think too much about that.

“The Lens of Time” from Writing Excuses

In my contemplations on time in storytelling, I revisited this podcast episode, which was recommended to me in my sister’s newsletter Nicoledonut. The episode explores how time shapes narratives beyond just plot structure, covering practical techniques of character memory, flashbacks and sensory shifts:

- Character memory and flashbacks: One of the hosts says she really thinks about how her character reckons with the time they are in with their own lives and also the time that the world is in around them. “Are they in sync? Are they moving forward in a world that’s moving forward with them? Do they want to hold back in a world where they love tradition, but the world wants progress?” (Sidenote: The example they give is the fight scene between Paul Atreides and Jamis in Frank Herbert’s Dune. DUNE MENTIONED!!)

- Magnified moments: Dilating time at a scene level, like in that fight scene, the effect of expanding out every single second, every step, every slice of the blade through the air is marking this fight—the first time Paul will kill a man (spoiler: but not the last!)—as a turning point in his young life.

- Sensory shifts: The interplay of two time concepts: the character’s awareness of time (the time that an event takes in the life of a character) versus the time it takes on the page (the actual amount of time that it takes a reader to experience it) can make time slow and speed, for example, the hosts point to lingering on the character’s experience, feeling all the things they feel, noticing all the things they’re noticing, and where they feel it in their body as a way to create this sense of dilating time for the reader.

How this has changed how I read

In a smattering of my recent reads, I’ve become way more attuned to time markers and find myself paying more attention to how different authors move their readers through time on the page:

- Hamnet: Maggie O’Farrell starts at the ending, deploying both a circular narrative and omniscient third POV to serve the tragedy of this story where the readers already know the ending. But her compression of long time alternating with the magnification of pivotal moments builds suspense and tension for the reader in learning how the characters will move through the story to arrive at the inevitable ending.

- Five-Star Stranger: Kat Tang’s narrative mostly moves linearly (in classic time), but a key memory/flashback for the narrator imbued throughout the story that is revealed to be the reason he gets into the rental stranger business in the first place. Tang also takes great care to emphasize physical descriptors, which does dual duty of revealing the narrator’s character through his masks, but also serves to move the reader through time.

- Interrogating “to what effect?” as a reader, asking why and how certain tempos or rhythms in fiction are serving the story (or not).

How this has changed how I write

*Jay-Z voice* TIIIME! I don’t get enough of it!

Okay but in all seriousness, I think the most significant way this interrogation of the “art of time” has changed my writing in this current project is being more conscious of how I’m handling time to reveal my characters’ inner worlds—whether through fear, anticipation, anxiety, or regret.

The portion of time a story chooses to narrate decides what its point is, how it gathers meaning, I repeat to myself. What its point is. What is its point?

In the short story I’d been working on, I started initially with a longer duration of time, covering childhood to young adulthood for my main character. By continuing to ask myself what the point of this story is, I kept trying to zoom in—especially since in a short story, space is so limited and every word needs to count. Was the thing I had come to say actually the last sentence of the 10,000 plus words I had written?

In trying to decide where to cut and how to tighten the frame of this short story, asking myself what details were significant enough to keep in, and which actions were better left to the reader’s imagination, I ended up writing a very different story than the one I actually wanted to tell. This realization was catalyzed by a conversation with my friend Ash (also an amazing writer), where after listening to me describe the story, my challenges, the time covered in the story and the time spent on writing the story, told me, “I’m so sorry. I think you’re actually writing a novel.”

Unfortunately, the story I think I want to tell does demand more time (who’s shocked?). What I'm interested in exploring is the suddenness of not being able to do the thing you love anymore, and who do you become as a person if you can’t be the very thing that defines you, and what would you give up to get it back?

Homework/generative exercises for the overachievers (me to me)

- From Chung’s lecture: Keeping in mind these different techniques of manipulating time in fiction (speeding up, slowing down, oscillating, collapsing/freezing), pick one of these to focus on. Beginning with the phrase, “Back then” and ending with “Today,” write five sentences that manipulate time by either speeding up, slowing down, oscillating, or collapsing/freezing it. Think about techniques such as varying sentence length, word choices, physicality, sensory detail, etc.

- From Writing Excuses: Change the time at which a scene takes place. Try to move something from day to night, or from spring to fall. What do you notice?

- From Bell in Refuse to Be Done: Read a scene or chapter that isn’t quite working, analyzing time narrated and time of narration as you read. Then try changing the time of narration, either by rewriting what you have or by adding to it.

In Life

“A story can arrange events in any order it finds useful,” Silber writes, “but it does have to move between then and now and later.”

It is true in fiction we have more freedom in arranging events out of order and greater precision in temporal manipulations, but is this not what we do in our lived lives as well? I’m constantly in the process of making and re-making meaning in my life, which shifts as I get older, as my narrated time expands, and my time of narration continues to advance.

The stories we tell ourselves also change with different vantage points: anticipation and anxiety about a new relationship is a different story when you’re just getting to know someone; regret and longing maybe becomes the new story if that relationship ends; contentment or happiness could be another way the story goes if the relationship progresses.

I love this simple framing—then, now, later—as a way to examine my own rituals and routines in my everyday life. As someone who writes and makes art, the “twinned substances” of “art life” and “lived life” that Bell presents as the driving forces of one’s imagination also demand a lens of time to meld, recombine, and work together to spark creativity and produce new ideas.

Some of the ways I structure my habits around then, now, and later include:

Then: Reflection and writing with temporal distance, but unfortunately the key is actually revisiting the past in a meaningful way (yuck).

Now: Keeping intermittent, half-started diaries and journaling, or recording voice memos to myself (lol), to preserve in-the-moment thoughts and feelings. I also take a lot of photos and videos, which capture the now in high visuals but lower emotional resonance (at least for me I find it hard to really conjure the feelings I had in a moment in time just by looking at my phone’s camera roll, mostly what I feel is my present disgust or nostalgia).

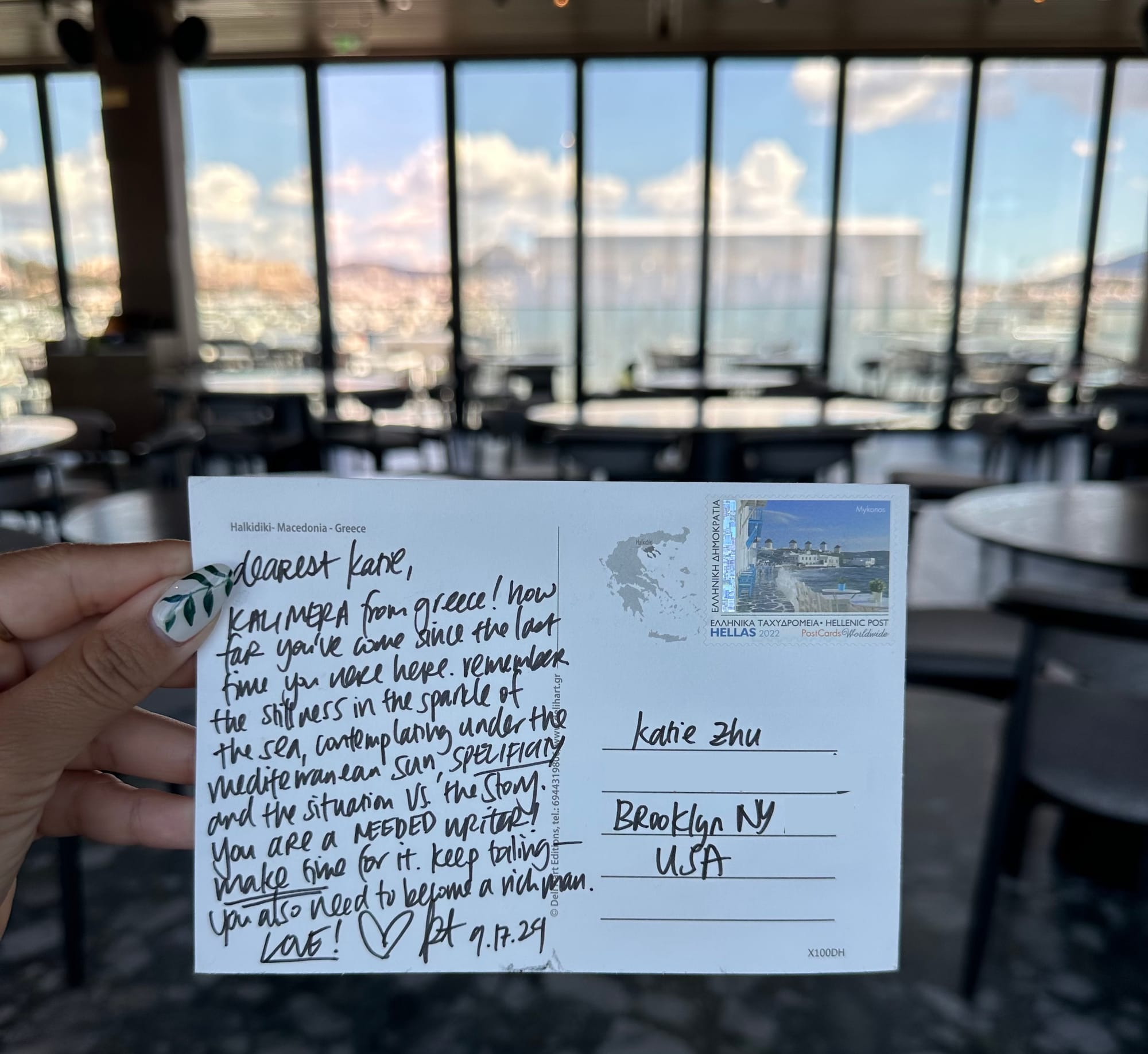

Later: I love to romanticize and create artifacts for my future selves. One small way I’ve started to do this in the last few years is always mailing myself a postcard when I travel. I write a small little missive, always beginning with “Dear katie,” and closing with “Love, katie”—which confused my friend Tyler when he was staying in my apartment. He told me later: “I was like oh, katie got a postcard! Wait, this is her handwriting… is she just writing to herself?” Well, yes!

Sanuki Time

This is a journal entry from my trip to Japan earlier in the fall (written in the “now” at the time, revisited as a “then”). I wrote this during my stay on the Art Islands, while staying in a beautiful traditional Japanese home in Kagawa prefecture.

10.10.25

Experience “Sanuki time” surrounded by the chirping of birds and the morning sun in a quiet environment overlooking the Seto Inland Sea and the Goshikidai countryside. Why not relax your mind and body with a stay in a 110-year old traditional Japanese house where you can forget about time?

You’ll be spending a relaxing countryside time at the foot of the fire-color pit. It is not a sightseeing spot, but there is no such thing as a country town with nothing. The refreshing air of the morning, and the relaxing life of the neighbors. It’s the “countryside” of all of you. You can enjoy it.

Would you like to heal your daily fatigue in an old fashioned village in Japan?

I will help you to have a memorable time.

No TV, no noise from the city. Why don’t you prepare your mind and body with an old house stay that forgets your time?

In a quiet environment with a view of the Seto Inland Sea and Satayama of Goshiki, you can experience the “Sanuki time” surrounded by birds singing and sunrise.

“Sanuki time”—A time outside of time, where the only demarcations of its passage can be gleaned through the shifting shadows as the sun moves throughout the day, the way the light moves through the windows, the chorus of birds chirping in the morning, with cicadas taking over the symphony by nightfall.

Sanuki time is sleeping with the sun and the moon, closing your eyes as darkness envelops the night and obscures any views of the outdoors, and then opening them as the first rays of dawn peek through the windows onto the soft notches of the tatami mats. I don’t know if it was something about the groundedness, the connection with the floor, the earth, but I grew into its comfort, sleeping more and more each night, reaching a glorious eleven hours on my third night here.

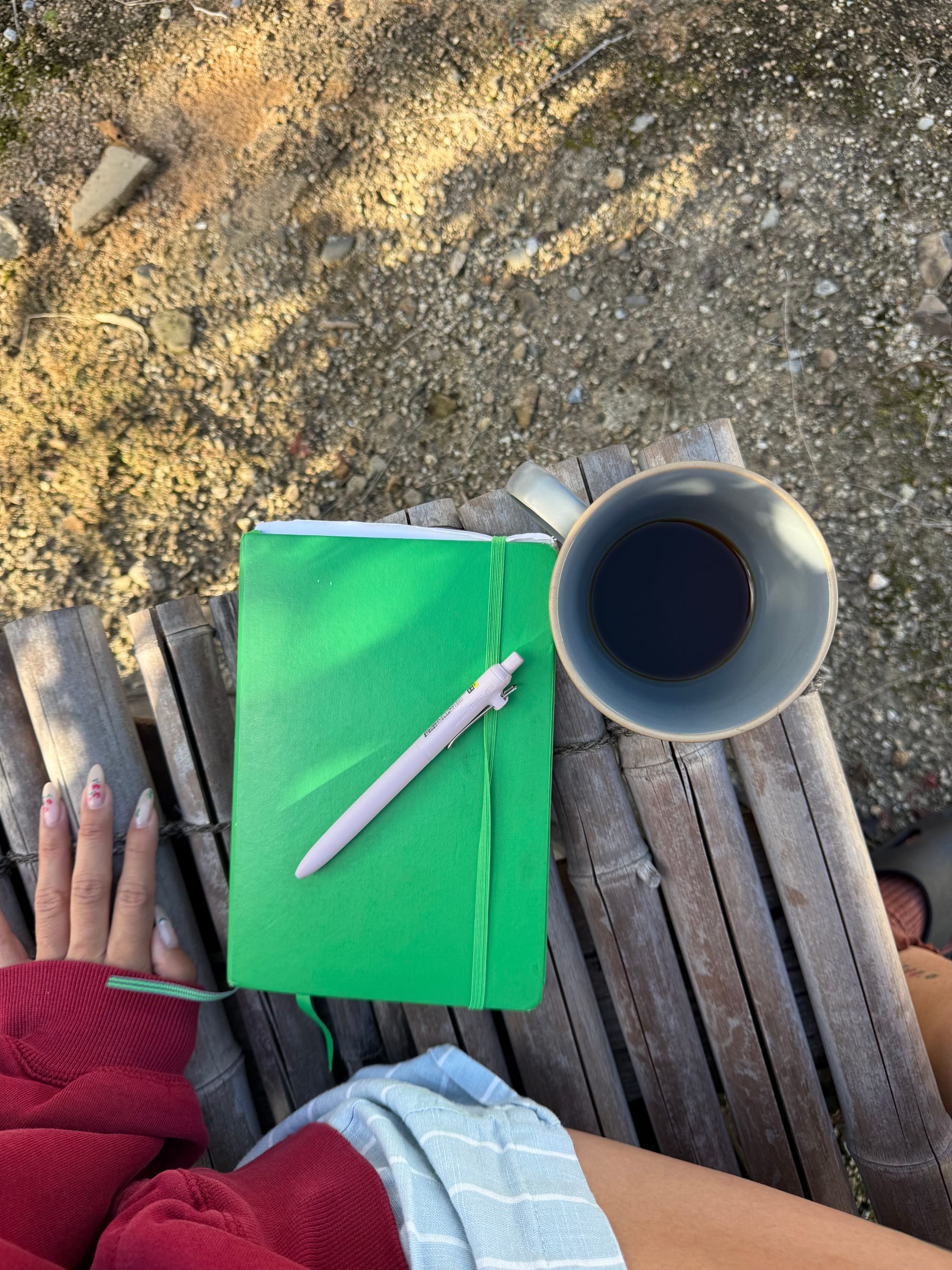

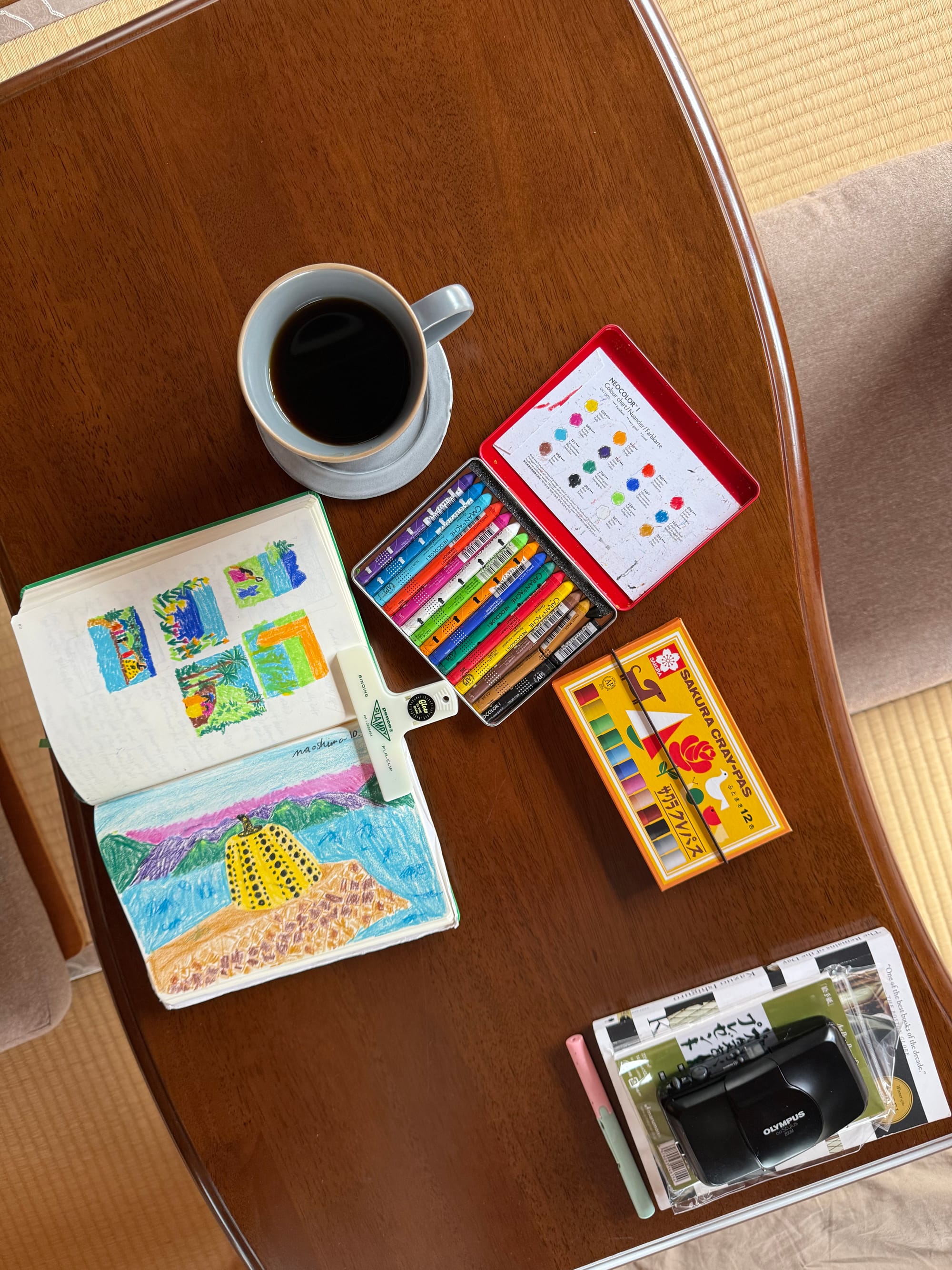

Sanuki time is also—unfortunately, for me—logging back onto the internet after a restful night outside of time and seeing I’ve missed not one, but two surprise screenings of Marty Supreme, contemplate drinking some bleach, but then take myself off kms alert the moment I step outside, mug of steaming coffee in one hand, notebook in the other, and remind myself that scavenging TikTok for Timmy crumbs is decidedly not what I should be doing in Japan. Sanuki time isn’t perfect this morning, but two mornings ago, it was rising from my tatami mat without looking at my phone, judging the color of the sky and the position of the sun that it probably had to be before 6 am, and drawing little one-inch pictures as the sun rose.

Sanuki time: Drawing vignettes with oil pastels and experiencing simple pleasures of making marks on paper under the sun and in nature, the complete surrender to the feeling of being inspired by art to make art again.

Sanuki time: Letting time wash away in a deep soaking bathtub, filled to the brim with aromatic bath salts, steaming my body in hot water that feels so cleansing.

Sanuki time is bringing my mind and body back to the present, rooted in the physical sensations that come with paying attention to the world around me, yes, but more crucially, how my mind feels when I interact with the world from a place of attentiveness, slowly, deliberately. It feels different. It will be memorable.

As Clémence Poésy’s character explains inverted time in Tenet: “Don’t try to understand it. Feel it.”

All in good time,

⏳ katie nolan ⏳

PS: Merry Chrysler!

—Ancient Chinese proverb, allegedly, quoted by two white guys

Eye: My place for recounting what I'm seeing — films, art, shows

Hand: Craft section for my writing or art projects

Heart: Essays and vignetty feelings à la Deborah Levy, or trying to be