Practicing Living

Issue 3: Lessons from my Beginner Acting class

“What is acting?”

My teacher, Scott Organ, posed this question on our first day of class. Most simply, it is saying and doing something in a place. But more than that, acting is living truthfully under artificial circumstances. All of us know how to do this, to some degree, on different occasions in our day to day lives. We live the most truthful version we can be under the circumstances of work, but this is a different version than the person who lives under the circumstances of getting dinner with a friend, which is a different version than the person who exists in the circumstances of being alone in their apartment.

“Why do we act?”

“To practice living,” Organ says. “Acting is the study of human behavior, and it allows us to experience emotions in a safe way.”

I really loved this framing, “practicing living.” A practice inherently gives you permission to play and experiment, but it also reinforces the idea that it has to be ongoing. There’s work involved in a practice, you have to show up and be consistent in order to practice living the life you want to live, to try on different selves, different hobbies, different reactions and emotions. It reminded me of the importance of art — whether acting, visual art, fiction — and this Ethan Hawke quote in particular:

“Most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about poetry, they have a life to live and they're not really concerned with Allen Ginsberg’s poems or anybody’s poems. Until their father dies, you go to a funeral, you lose a child, somebody breaks your heart, they don’t love you anymore, and all of a sudden you’re desperate for making sense out of this life and “has anybody felt this bad before, how did they come out of this cloud?” Or the inverse, something great. You meet somebody and your heart explodes, you love them so much you can’t even see straight. And that’s when art’s not a luxury, it’s sustenance.”

So why did I, someone who is famously trying to never be Perceived, decide to sign up for an acting class? Well as we know, I love hobbies. I originally took acting to inform my writing, specifically working on writing dialogue, but I also wanted to push myself out of my comfort zone and try something new. And it worked! I arrived at my first class 30 minutes early, which has truly never happened in my life, so, mission accomplished.

My friend Alice (a talented thespian) recommended The Barrow Group as a great beginner class that was very structured and tangible: over 10 weeks, we started with games and exercises that built into tools, then moved into story structure and script analysis, all of which culminated in scene and script work. We were all expected to do at least 1 monologue and 1 scene (with a partner).

So much of what resonated in this class was Organ’s teaching style (he’s also a playwright and screenwriter) and The Barrow Group’s overall acting philosophy. It is very Ratatouille, “anyone can cook,” rooted in the belief that anyone can act, and acting should be easy! It should be fun!

While this pedagogy obviously helped me begin to act, I’ve found that so many lessons apply beautifully to building and living a creative life overall.

Living in the circumstances

The foundation of my acting class was the value of circumstances, and how as actors, we should lean into circumstances instead of planning behavior, which Organ calls the “enemy of spontaneity.”

He walked us through a set of 3 simple questions before going into a scene:

- What are the circumstances?

- Review the circumstances, let them wash over you

- Live in the circumstances, but leave yourself open to play and fun – because that’s where the magic happens

As ~ actors ~, letting the circumstances play on us, instead of playing on the circumstances, is what distinguishes a good performance from a bad one. A good performance feels real, like you’re in the story and you feel the emotion of the characters and the scene. Organ says that as an audience member, he doesn’t want to notice the acting: “When you walk into a building, you don’t notice the studs, even though they're holding up the building. That’s what makes a good performance.”

Living in the circumstances, but leaving yourself open to happy accidents, to play and spontaneity, is that not what life is all about? It’s a reminder I now return to in my writing practice.

Letting go of ideas

Once you understand the circumstances, the next step is to let go of any “ideas” you may have about your character. Trust that the story is intact, and let go of the weight of trying to tell the entire story, and just show up and be real within it.

You have to show up prepared, and really listen, but Organ always reminded us that you don’t have to respond right away. You can let the circumstances settle in.

He shared an anecdote about a character he was playing who is a narcissist. “But I was thinking, he probably doesn’t know he’s a narcissist. I had to get back to a place of not judging my characters.”

Being wary of getting ideas early on – of what a scene should be or how it should be played – helps actors have honest, spontaneous, real behavior. I’ve found this in my writing, too, that often my initial “idea” of what a character should do or say isn’t actually what that character wants.

Avoiding patterns early on

When you stand up on stage to give a performance, you go to the safest place, and the safest place is often where the patterns you’ve established are.

Organ pushed us to not practice in patterns, because that can get you stuck in a certain kind of performance, which can make you unwilling or incapable of adjusting to a notes and feedback.

When it comes to writing, some degree of patterns and prior art can be helpful as a starting point, especially in structure. Repetition as a literary device can also be deployed effectively when it serves the narrative, but I think the trick is to avoid always doing the same thing in the work, because that honestly just makes for a very boring story and very formulaic writing. Minimizing overuse of certain words and catchphrases in my writing is often the first thing I edit in revisions; I try to vary sentence lengths and sentence structure; I deliberately shift points of view from character to character when I feel stuck. (Many of these exercises I learned from Ursula K. Le Guin’s Steering the Craft and return to time and time again).

Avoiding patterns is also a life lesson I’ve learned after The Big T (trowma). In my own relationship to creativity, I’ve had to work through different goals and expectations in how I show up for myself and accept that I need different routines and strategies depending on my energy and mood. For example, my depressive states are not conducive to me making art, but perhaps journaling dramatically about how I’ve never achieved anything in my life and never will again can be the adjusted output for that mental state.

In the same way as when actors memorize lines, they shouldn’t say the lines the exact same way every time, I’m finding that each time I show up to the page – to write, to draw, to make marks – it is beneficial to do something different for each go around. It might just unlock something surprising but inevitable.

Story structure and script analysis

I’ve learned story structure from writing classes, but studying it through the lens of acting gave me a new appreciation for narrative arcs. It’s important for actors to study the shape and movement of a scene because it helps inform your understanding of the circumstances.

“I often return to script analysis as an actor and writer, particularly thinking about the shape of a scene,” Organ says. “Where does the scene end? Okay, so we probably start somewhere far away from there. A scene is a journey and change happens within the scene.”

For deeper scene study, we learned how to analyze the 5 W’s — who, what, when, where, and why — to help actors know what to do and how to prepare beforehand. For example, for my monologue, when asking the question, “Who’s in this scene, and who’s in the vicinity?” helped me uncover that my character’s dying father was in the next room of a New York City apartment. The scene was a dramatic one, and this analysis informed a choice in my performance to lower my voice when my character started mentioning DNRs and matters of the estate, so her father wouldn’t overhear.

Spare scenes and the hottest circumstances

Spare scenes are scenes intentionally written to be completely devoid of context, allowing you to add the circumstances. When you don't know the circumstances and can create them, “choose the hottest circumstances,” Organ says. “What’s going to make you care the most deeply? Make it as personal as you can, and get really specific about it.”

Specificity, specificity, specificity. Truly goated writing advice. Jemimah Wei, author of the novel The Original Daughter, builds deep precision and specificity into her characters and settings. At her book launch at Yu & Me Books, she talked about how she builds characters by journaling from every character’s own POV to build an “emotional synopsis.” This allowed her to explore the emotional story of her characters between drafts. Her actual draft was around 85,000 words, but she says in total, she wrote closer to 500,000 words for the novel. I bow down in awe. The Original Daughter is set in Wei’s home country, Singapore, and she also discussed the importance of time and place as its own character. Geography, yes, but also place in the emotional sense of the things we carry with us and the narratives imbued into a specific place. Wei also emphasized the power of yapping in her research, recounting how she befriended a lot of residents in a specific building in Singapore as she was researching: “It was important to know which apartment this character lived in, which unit.”

I’ve started to practice a version of “spare scenes” as a writing exercise too, as recommended to me by my soon-to-be brother in law and screenwriter extraordinaire Evan: Journaling on the train and watching people’s behaviors, choosing specific and hot circumstances to explain why they just flashed a smile from seeing something on their phone, or imagining an unhinged reason for why the music or podcast they’re listening to is making them furrow their brow.

Other Barrow Group tools

Seth Barrish, The Barrow Group’s co-artistic director, wrote a great book compiling all the tools they teach in their classes. A few other ones that we practiced when doing monologues and scenes were:

- Conversation exercise: You start just by talking normally and having a regular conversation, then someone will “slip you in.” Once you “slip in,” you and your scene partner (or just you if it’s a monologue) will start saying the lines, but the point is to notice if you’re saying it differently from how you would normally converse. I’ve actually used this tool to get myself into writing character dialogue, and I’ve found it to help me just say what I mean more realistically (instead of trying to Write which often comes out stilted).

- Don’t ignore me: With a rehearsal partner, have them ignore you and as you say your lines, you increasingly are trying to not be ignored and get their attention. A fun one to raise the stakes and drama.

- Time limit on scene: This can make the scene feel more urgent and high stakes. I also regularly do this in my day-to-day life to gaslight myself into completing tasks (see: pomodoro technique, aka the only way I was able to write this newsletter).

- Doing things: This is definitely my favorite and the most versatile tool I’ve used in my fledgling acting practice. It works in the context of learning lines (doing an activity while you memorize), but also in the context of a performance (doing things, and saying things while doing things can make the scene feel more realistic and lived in).

- Making a list: Essentially speaking as though you’re rattling off a to-do list. I used this one for another monologue I did, with very high stakes: my character had just murdered her husband (good for her!) My teacher suggested I try this tool to apply a low stakes affect to the scene, which helped heighten the comedic tone of the scene.

Practicing living a creative life

“Writing a novel is a long exercise of extended psychological vulnerability with yourself and being alone,” Wei says. “The novel becomes the lens through which you see the world.”

If I was more diligent about working on my writing projects, maybe my “novel” would be my lens. But for now, this class has given me a new lens through which I not only see, but experience the world.

I’m reminded again of acting as “practicing living” and the importance of allowing space for spontaneity and having fun. This a reminder! Things should be fun!!

Committing to creativity is a practice and the rigor is in showing up. But to do the work well, you have to get comfortable with being bad, writing the worst words ever strung together in the history of the English language, or giving the most cringe-inducing performance. So much of life is being cringe and being okay with being cringe, and hopefully laughing through it. I'm practicing living a creative life. I endeavor to show up each day, leaving myself open to play. Hoping for magic. Because we need that, all of us.

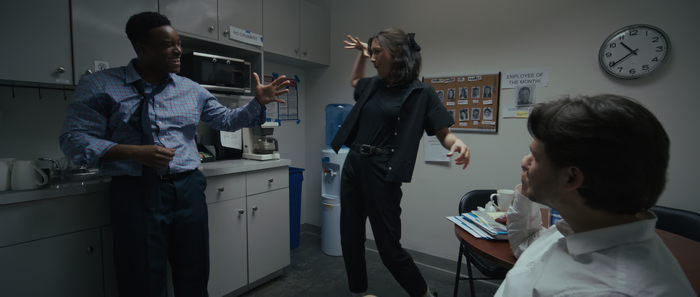

Thank you for reading katie mag. If you enjoyed this issue and you have the means, please consider becoming a patron of the arts and supporting The Audit, a dark comedy short about what your job is doing to your soul, starring Devon Werkheiser from Ned’s Declassified School Survival Guide. My aforementioned BIL/screenwriter extraordinaire Evan produced it!

“My favorite thing about the movie short is, like, it feels like a movie short. It feels like a real, like, you know, go-to-the-theater movie short.” —Harry Styles, basically

♥,

katie (p.g.a.), Associate Producer of The Audit 😎

—Ancient Chinese proverb, allegedly, quoted by two white guys

Eye: My place for recounting what I'm seeing — films, art, shows

Hand: Craft section for my writing or art projects

Heart: Essays and vignetty feelings à la Deborah Levy, or trying to be